In September 1935, the fashion magazine “Harper’s Bazaar” published an editorial titled “The Bushongo of Africa sends his hats to Paris.” This editorial included Adrienne Fidelin, the first ever Black female model to appear in a major American fashion magazine.

While Fidelin’s inclusion in this editorial is important and historical for a multitude of reasons, the editorial would unconsciously also hold a greater and broader significance, which would ultimately reflect the effects of colonialism and the West’s exoticism of African culture and its peoples.

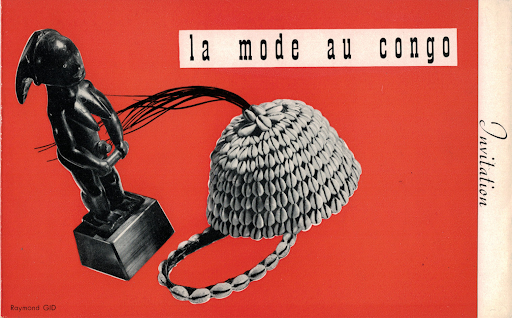

The editorial covered a collection of headdresses that originated from Central Africa’s Congo Basin, which was exhibited at France’s Colonial Exposition of 1931. The headdresses were part of a 50-piece collection from French milliner Lily Daché, who pioneered French millinery in the 1930s and 1940s.

Each headdress is individually unique, exemplifying the lush, complex symbolism of many Indigenous communities within Central Africa, including the Kuba and Bushongo people. Across Africa’s long and rich history, headdresses have held significant cultural importance in sub-Saharan African societies.

The Kuba and Bushongo see headdresses as an important part of body adornment that can hold a multitude in forms of expression and communicate one’s status and culture. These headdresses exemplify the differing ways many Central African communities utilize varying forms of colors, patterns, motifs, and natural materials.

The exact date of each headdress is unknown, as no known record of Dachéc purchase has been discovered, but most historians date these headdresses around the periods of the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century. It’s even more unclear how and when the headdresses left the Congo and how Dachéc was able to possess the collection, leading many to question whether the headdresses were “given” to Dachéc or were taken from their original owners, which has historically been the case when it comes to acquisitions of African art by Europeans buyers.

The creation and acquisition of the headdresses coincides with the brutal leadership of Belgium’s colonial rule over the so-called- Free Congo State, in which under the leadership of King Leopold II of Belgium, between the period of 1885 to 1908, over ten million native Congolesians were killed, becoming the deadliest genocide under a colonial regime.

The sheer brutality that native Congolesians experienced under Belgian rule goes unmentioned in the 1935 “Harper’s Bazaar” editorial that refers to the headwear as “exotic primitive native chic”, and besides the inclusion of Fidelin, are all modeled on White individuals.

The “otherness” of the headwear, which had been created to display one’s status and other utilitarian purposes of adornment, was transformed into a Western context that used stereotypical and racist terminology that labeled African peoples and their creations as “savagery” and propped them up as a fun fashionable fad.

As told by Life Magazine, an article reviewing Dachéc’s collection under the title of “Africa’s Belgian Congo Sets the Style of Hats for American Women” claimed that Dachéc’s collection “threatens to become the ‘African style’ in hats this fall and winter.”

Dachéc herself even drew “inspiration” from the collection, creating several pieces that used many of the characteristics of the native Congolese collection, such as the designs and materials that were titled by fashion critics as “coloniale moderne aesthetic.”

In the eyes of the media, Dachéc had created a new aesthetic and an exciting fashionable fad that had never been seen in “civilized” Europe and America.

The collection would also make an appearance in the Fascist-leaning German weekly magazine “Koralle”, which published a satirical article covering the collection in 1937 titled “Is New York located on the Congo River?” (Liegt New York am Congo?). Photographs of the hats on White models were accompanied by racist stereotypical cartoons that underscore not only the intense bigotry of the magazine but also the persistent notions of savagery that the headdress represented of Central African people.

The collection and the reaction garnered by White European and American media reflect how colonialism has shaped history and Western societies’ perceptions of African people and countries.

Even though European colonialism may be “over” and countries such as France and Belgium have acknowledged their history in the dehumanization of African peoples, notions of Africa’s “primitiveness” still exist. The violence and exploitation of Africa and African peoples that was the direct result of European powers is still felt and is one of the many direct factors of the ongoing genocide in Congo that has claimed more than six million people’s lives.

While the headdresses have largely been forgotten by the mainstream, the collection has showcased how Africa’s material culture has been deemed “primitive” and “savage” by the West, but at the same time appropriated and transformed into exotic “chic” modes of fashions that echo White supremacy and brutal colonialism’s role in shaping Central Africa’s/Africa history.