Previously this year, on Feb. 18, 2025, researchers at Mie University in Japan developed an experimental “cure” for the popular genetic disease known as Down syndrome. Although it is not a proper cure yet, the success of the experiment is still a revolutionary breakthrough in scientific history.

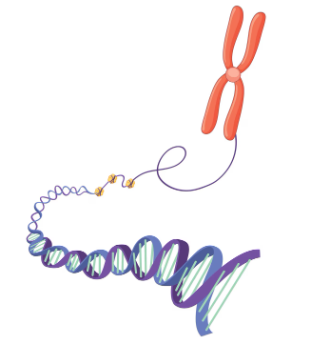

Down syndrome is a genetic condition that affects 1 in every 700 newborns. This disease can be found in individuals who are born with an extra copy of chromosome 21 instead of the usual two copies, resulting in birth defects. This disorder affects the individual’s brain, physical appearance, and the way their body develops as they age, which can lead to enhanced susceptibility to future diseases, including a congenital heart defect.

Mie University acknowledged the struggles that this group of individuals goes through, and determined that they would attempt to help them in any way, shape, or form. The additional chromosome is the main cause of this genetic condition, so researchers knew that they had to start there.

According to the Mie University Research Navi website, the research team was led by Dr. Ryotaro Hashizume (a scientist who was a member of the Unit for Genomic Manipulation and Technology Development) who succeeded in creating an experimental pioneering technique for eliminating the extra copy of chromosome 21 in cells via the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology.

Genome editing has been around since the early 1980s, but the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology was first introduced in 2012. After countless failed attempts, the research team at the university decided to utilize the CRISPR-Cas9 method and hone it so that it only targets chromosome 21, also known as trisomy 21.

Once the team employed the technique, they began to see results almost immediately. The group analyzed the petri dish full of lab grown cells, and attempted to eliminate the extra copy of trisomy 21.

Based on the information given in the Mie University website, the team had a success rate of about 37.5 percent, along with a report stating that in the cells with normalized chromosomes, various characteristics such as gene expression patterns, cell proliferation speed, and the antioxidant capacity were all restored to regular levels. Since the experiment succeeded, the scientists conducted another series of tests, but this time, they tested CRISPR-Cas9 on skin fibroblasts (Mature, non-stem cells) taken from people with Down syndrome.

MedTour, a Ukrainian International Healthcare Group, has an article titled, “Japanese scientists have developed a method for removing the chromosome associated with Down syndrome” that adds to the story. The article adds that after the previous successful experiment, the colleagues decided to perform another one using CRISPR to test on the donors’ skin fibroblasts.

Similar to the last experiment, these tests were also a success. The gene-editing method was able to efficiently extract the extra chromosome in multiple cases.

Upon further inspection, the scientists were able to conclude that after the extra chromosome was removed, the genes tied to nervous system development were more active, and the ones related to metabolism were less active. After the removal of the extra trisomy 21 from these cells, the researchers reported that the corrected cells grew back faster, and they also had a shorter doubling time than untreated cells.

According to the New York Post, multiple reports have shown up, claiming that the experiment advocates for the concept that removing the extra chromosome may possibly help with the biological strain that slows down cell growth. If the idea is true, then this discovery has the power to change several lives.

However, once more research was conducted, it was discovered that the CRISPR treatment has some major drawbacks. According to the data collected by Hashizume and his team, the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology is also capable of damaging healthy chromosomes, which means that instead of fixing the issue, it can terminate an entire chromosome.

Due to this conclusion, the research team is further re-evaluating their experiments and collecting more data to help ensure that their work can be used as regenerative therapies and treatments in the future instead of escalating the issue.

Despite the hopeful efforts of Hashizume and his colleagues, the topic has recently become quite controversial amongst various parts of the world. Many people have concerns about the ethics of genetic manipulation, the nature of the condition itself, and whether Down syndrome is really something that needs to be cured.

The National Institute of Health distributed a questionnaire, or a poll, to 101 parents in British Columbia, Canada, in order to gather data about whether most parents want their children to be cured of the disease, or if they find the treatment to be unethical. Out of the 101 participants, only a shocking 41% responded that they would want their child to be cured of the genetic disease if it were possible.

About 37% of the responses claimed that they would not consider the cure as an option, regardless of its efficiency. These are the families who believe that there is no need for a cure, and that people with Down syndrome are beautiful in their own way.

As the research team from Mie University continues to build upon their collected data and successful experiments, they claim that they will continue to do whatever it takes to form therapies and cures for people with Down syndrome. Even after facing constant backlash, the team is refusing to give up and has committed to conducting many more experiments, all while collecting new data about the effects that CRISPR-Cas9 has on chromosome 21.

More information regarding cell function, genome editing technology, CRISPR-Cas9, trisomy 21, and the effects of post-gene therapy on patient skin cells continue to be discovered each passing day as the students from Mie University aim to make the world a better place for those individuals who have Down Syndrome. Their one and only goal is simple-to delete Down Syndrome and make the quality of life simpler and easier for those who have the genetic condition.